In this essay, Derrida makes a number

of strongly Wittgensteinian points about meaning and the use of

language.

He notes that a sign always relies on a history of use in so far as it has a meaning, but that this history does not in and of itself constitute an unambiguous precedence. Theories with a strong or even mentalistic concept of “literal meaning” — Derrida duscusses Husserl and Austin — thus always have to jump through a lot of hoops in order to make it seem as if it were obvious how this word ought to be used in all future cases.

He notes that a sign always relies on a history of use in so far as it has a meaning, but that this history does not in and of itself constitute an unambiguous precedence. Theories with a strong or even mentalistic concept of “literal meaning” — Derrida duscusses Husserl and Austin — thus always have to jump through a lot of hoops in order to make it seem as if it were obvious how this word ought to be used in all future cases.

The Winding Road to Theory

He arrives at this conclusion by a

somewhat strange route over a discussion of the concept of “writing.”

According to Derrida, there is a classical philosophical theory which

singles out writing as being different from speech in that it

essentially involves a lot of peculiar absences — the physical

absence of the writer, the somewhat vaguely defined role for the

reader, and even the possible absence of a communicative intent in

the writing itself.

However, he goes on, these features are in fact present in all communication, so we should really count speaking as a kind of “writing” as well if we take this definition literally.

However, he goes on, these features are in fact present in all communication, so we should really count speaking as a kind of “writing” as well if we take this definition literally.

We don't, of course, but the point is

well taken: When a sign means something, it is because it echoes

something else in the past.

There is therefore an essential tension between the observation that signs have meaning because they conform to a tradition of use, and the assumption that signs express inner, conscious, authentic intentions. Declaring a meeting open or declaring somebody husband and wife always is kind of theatrical, and the attempt in Husserl and Austin to ban all theatrical or “non-serious” uses of language from playing a role in the theory is therefore doomed from the outset.

There is therefore an essential tension between the observation that signs have meaning because they conform to a tradition of use, and the assumption that signs express inner, conscious, authentic intentions. Declaring a meeting open or declaring somebody husband and wife always is kind of theatrical, and the attempt in Husserl and Austin to ban all theatrical or “non-serious” uses of language from playing a role in the theory is therefore doomed from the outset.

Why This Post is So (Damn) Long

|

| Book cover; from Wikipedia. |

So I'll try something different here: I'll go through the text,

literally page by page, trying to paraphrase everything he says in

readable, English prose. If anybody finds this blasphemous, then I refer to that French philosopher who says that

nobody owns the meaning of a text.

I'm following the page numbers as they appear in Limited Inc. Scans of the text is available from several university websites (e.g., here, here, and here).

I've not followed Derrida's headings, but rather divided up the text into some smaller chunks. This is partly to give the argument some structure and partly to give you some breathing space.

I've not followed Derrida's headings, but rather divided up the text into some smaller chunks. This is partly to give the argument some structure and partly to give you some breathing space.

The Problem with Communication, Context, and Writing

The Problem of Communication, pp. 1–2

Derrida warms up with some reflections that are quite weakly related to the rest of the essay: We might, he says, be tempted to say that the invention of writing extended spoken communication into a new medium. But this presupposes a concept of "communication," and we cannot necessarily take this for granted.

The word "communication" can refer to the effects of physical forces as well as the effects of meaning. This might suggest that we can think of the concept of linguistic communication as a metaphorical extension of a literal concept of physical communication.

However, Derrida disapproves of this suggestion on the grounds that

- he finds the whole idea of "literal meaning" suspect;

- he considers it circular to base a theory of meaning on a theory of meaning.

The Problem of Context, pp. 2–3

Derrida thinks that there are indeed some problems with the seemingly unproblematic notion of "communication," and he locates these problems more precisely in the concept of "context."

|

| Politeness is notorious for depending on context in subtle ways. Here, etiquette icon Emily Post sidesteps the issue by giving a cut-and-dry prescription without any qualification. (From Etiquette, Ch. 28) |

He asks:

But are the conditions of a context ever absolutely determinable? … Is there a rigorous and scientific concept of context? (pp. 2–3)

Lest you should think that the answer is yes, he asks an even more leading rhetorical question:

Or does the notion of context not conceal, behind a certain confusion, philosophical presuppositions of a very determinate nature? … I shall try to demonstrate why a context is never absolutely determinable, or rather, why its determination can never be entirely certain or saturated. (p. 3)

According to Derrida, this demonstration will

- raise suspicions about the concept of context;

- change the way we understand the concept of “writing”; specifically, he will question the idea that writing is a kind of transmission of information.

If Speech is Like Writing, We have a Problem, pp. 3–4

As stated above, Derrida notes that a lumping together speech and writing presupposes a unifying concept of communication:

To say that writing extends the field and powers of lucutory or gestural communication presupposes, does it not, a sort of homogenous space of communication? (p. 3)

If indeed there is such a homogenous space, then speech and writing

should share most features. However, he will first argue that the "classical" theory of writing will claim that they are substantially different, and then that they in fact are quite similar after all.

The "Classical" Theory of Writing

Condillac on Writing, pp. 4–5

In order to sketch what the tradition has to say about writing, Derrida provides a couple of quotes by the French Enlightenment philosopher Étienne Condillac (1714–1780), specifically from his Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge (1746).

|

| Condillac; from zeno.org. |

Men in a state of communicating their thoughts by means of sounds, felt the necessity of imagining new signs capable of perpetuating those thoughts and of making them known to persons who are absent. (p. 4)

This passage comes from Part II, Section I, Chapter 13, §127 of Condillac's Essay. In the 2001 translation that I have linked to above, the word "absent" does not occur, but it does in fact in the French original.

Derrida thinks of this hypothetical origin of language as an explanation in terms

of "economy," that is, practical concerns.

Comments on Condillac, p. 5–7

Derrida again emphasizes the role of

"absence" in Condillac's discussion. He stresses that

- it is characteristic of writing that it continues to cause effects even after the departure of the writer;

- to Condillac, absence is a gradual thinning out of presence (as in picture > symbol > letter).

He also repeats that Condillac is just one example of this theory, and that others could be given.

The Grand Claim, Part 1

Speech Might Be A Kind of Writing, p. 7

Derrida then proposes two "hypotheses":

- All communication presupposes a kind of absence; so if writing is special, it must be because it presupposes an absence of a special kind.

- Suppose we find out what this special kind of absence is, and suppose that it turns out to be shared by all other kinds of communication too; then there must be something wrong in our definitions of communication, or writing, or both.

This is a somewhat curious rhetorical somersault: First, Derrida has to sell us the rather unconventional idea that there is a classical theory of writing which defines writing in terms of a special kind of "absence." Then he has to shoot down that theory again.

Writing is Iterable, pp. 7–8

| |

| A swastika mosaic excavated from a late ancient church in contemporary Israel. If there ever was an "overdetermined" sign, this symbol must surely be an example. (Image from Wikipadia.) |

The possibility of repeating and thus of identifying the marks is implicit in every code, making it into a [grid] that is communicable, transmittable, decipherable, iterable for a third, and hence for every possible user in general. (p. 8)

Here is another way of saying it: If

a sign really means something, then other people can use it for their own purposes in other contexts. If they can't, it doesn't really have a meaning:

To write is to produce a mark that will constitute a sort of machine which is productive in turn, and which my future disappearance will not, in principle, hinder in its functioning … (p. 8)

Alleged Consequences of the Iterability Claim, pp. 8–9:

This iterability theory of writing has, according to Derrida, four consequences:

- It detaches writing from mentalistic notions like consciousness, intended meaning, etc. The theory is inconcsistent with the notion of "communication as communication of consciousnesses" or as a "semantic transport of the desire to mean" (p. 8).

- It provokes "the disengagement of all writing from the semantic or hermeneutic horizons which … are riven by writing" (p. 9). What he means is perhaps that iterability is different from "meaning" in some limited, conventional sense.

- It detached writing from "polysemics" (p. 9). Like the previous point, this could mean that the open-endedness of future use and citations is different from ambiguity of the more familiar kind, but I really don't know.

- The concept of context becomes very problematic.

He says he will come back to all of

these points later, but I don't know

what he's referring to.

The Grand Claim, Part 2

The Characteristics of “Writing,” p. 9

At this point, Derrida wants to "demonstrate"

that the iterability property is found in

other kinds of communication in addition to writing, and, more generally, across "what

philosophy would call experience" (p. 9).

Continuing his explanation of what he thinks Condillac is saying, he singles out three properties that writing is supposed to have according to the "classical" theory:

Continuing his explanation of what he thinks Condillac is saying, he singles out three properties that writing is supposed to have according to the "classical" theory:

- Writing subsists beyond the moment of production and "can give rise to an iteration in the absence … of the empirically determined subject who … emitted or produced it." (p. 9)

- Writing "breaks with its

context," where context means the moment of production,

including the intention of the writer:

But the sign possesses the characteristic of being readable even if the moment of its production is irrevocably lost and even if I do not know what its alleged author-scriptor consciously intended to say at the moement he wrote it, i.e. abondened it to its essential drift. (p. 9)

So once you write a sentence down, you lose control. - These breaks are related to the fact that writing is placed at some distance from the "other elements of the internal contextual chain" (p. 9). Presumably this chain is supposed to consist of things like the writer, the time of writing, the intention, etc. Derrida calls this the "spacing" of writing.

|

| The Lincoln memorial, finished 1922, mimics Roman architecture mimicking Greek architecture; picture from Wikipedia. |

All Communication is Writing, p. 10

After having made these remarks about the alleged classical theory, Derrida goes on to ask whether the classical characteristics of writing really are characteristics of all communication:

Are [these characteristics] not to be found in all language, in spoken language for instance, and ultimately in the totality of "experience" … ? (p. 10).As an example of iterability in spoken language, he notes that we need to be able to recognize a word across "variations of tone, voice, etc.". This means that every new application of the word has to be recognized as an echo or citation of some earlier event. Thus, meaning must involve citation, since

… this unity of the signifying form only constitutes itself by virtue of its iterability, by the possibility of its being repeated in … the absence of a determinate signified or of the intention of actual signification, as well as of all intention of present communication. (p. 10).

These iterability conditions are, says Derrida, really characteristic

of writing according to the classical theory. Hence, spoken language is a kind of

"writing":

This structural possibility of being weaned from the referent or from the signified (hence from communication and from its context) seems to me to make every mark, including those which are oral, a grapheme … (p. 10).

Again, he generalizes this to

experience without going to much into the topic:

And I shall even extend this law to all "experience" is general if it is conceded that there is no experience consisting of pure presence but only of chains of differential marks. (p. 10)The idea is, presumably, that in so far as experience is mediated or interpreted, it is a kind of writing.

Critiquing the Tradition, Part 1

Husserl on Nonsense, pp. 10–11

|

| Husserl; from the Lancet. |

- Signs that have a clear meaning, but no current referent (I say "The sky is blue" while you can't see the sky);

- Signs that fail to have a meaning because they are

- superficial syntactic symbol manipulation, as in formalistic mathematics;

- oxymorons, like "a round square";

- word salad, like "a round or," "the green is either," or "abracadabra."

This discussion refers to

Volume II of Husserl's Logical Investigations. Specifically, the relevant parts of the text are Investigation I, §15 and Investigation IV, §12.

Derrida on Husserl, p. 12

Derrida notes:

But as "the green is either" or "abracadabra" do not constitute their context by themselves, nothing prevents them from functioning in another context as signifying marks. (p. 12)

As an example, he mentions that the

word string "the green is either" is used by Husserl as an

explicit example of agrammaticality — so it did after all have a use in language. (Consider also how the sentences "Colorless green

ideas sleep furiously" or "All your base are belong to us" have taken on a life of their own and can now be echoed or referenced.)

This illustrates, he says,

the possibility of disengagement and citational graft which belongs to the structure of every mark, spoken or written … (p. 12).

Even more explicitly:

Every sign … can be cited, put between quotation marks; in doing so it can break with every given context, engendering an infinity of new contexts in a manner which is absolutely illimitable. (p. 12)

He goes on to say that a sign which did

not have this property of citationality or iterability would not be a

sign.

Critiquing the Tradition, Part 2

Things Derrida Likes About Performatives, p. 13

After having discussed Husserl, Derrida moves on to Austin. He wants in particular to talk about the notion of performative speech acts.

This concept, he says, should interest us for the following reasons:

- Every proper utterance is in a sense performative.

- The concept of performatives is a "relatively new."

- Performatives do have referents in the usual sense.

- The discussion of performatives made Austin reanalyze meaning as a concept of force (and this brings him, says Derrida, closer to Nietzsche).

These four features of performatives undermine the

traditional communicative concept of meaning, according to Derrida.

Austin's Blind Angle p. 14

In spite of this subversive potential of performatives, Austin fails to realize that spoken language has the same "citationality" as writing, and this causes problems for his analysis again and again.

Specifically, he holds on to his mentalistic understanding of meaning. The

"total context" that Austin has to keep referring in his discussion always contains

consciousness, the conscious presence of the intention of the speaking subject in the totality of his speech act. As a result, performative communication becomes once more the communication of an intentional meaning … (p. 14)

Infelicity is Structurally Necessary, p. 15

|

| Austin; from University of Washington. |

On one hand, Austin can thus recognize that

… the possibility of the negative (in this case, infelicities) is in fact a structural possibility, that failure is an essential risk of the operations under consideration; (p. 15)but on the other hand, he

… excludes that risk as accidental, exterior, one which teaches us nothing about the linguistic phenomenon being considered. (p. 15)

Repeating that point once more, Derrida states that:

- Austin recognizes that there are ritualistic aspects to the context of a conventional performative speech act, but not that there are ritualistic aspects to meaning itself. "Ritual," Derrida asserts, is "a structural characteristic of every mark." (p. 15)

- Austin does not take the possibility of infelicity seriously enough, and he consequently fails to recognize that it is "in some sense a necessary possibility." (p. 15).

Critiquing the Tradition, Part 3

Serious and Non-Serious Language, pp. 16–17

To illustrate these points further, Derrida quotes a passage from Austin's work in which he says that theatrical or joky language is “parasitic” on the more serious uses of language.

For, ultimately, isn't it true that what Austin excludes as anomaly, exception, "non-serious," citation, (on stage, in a poem, or a soliloquy) is the determined modification of a general citationality—or rather, a general iterability—without which there would not even be a "successful" performative? (p. 17)

Do you want me to answer? Or is this a questions-only conversation?

A Private Language Argument, p. 17

At this point one might interject, Derrida says, that “literal”

performatives are successfully executed all the time (opening a meeting etc.), so

shouldn't he take care of those cases before he starts talking about

theatrical deviations?

Not necessarily, Derrida says: Even a private language will

have to conform to some internal standard, and even an event that happens

only once might implicitly be a version of something else.

The Necessity of Infelicity Again, p. 18–19

In effect, Austin thus depicts "ordinary language" as surrounded by a ditch which it can fall into if thing go awry. But according to Derrida, this is a somewhat misleading picture in that the "ditch" is a necessary shadow of meaning.

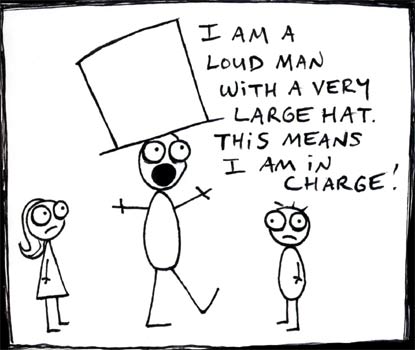

|

| A possibly infelicitous speech act; by Don Hertzfeldt. |

Could a performative utterance succeed if its formulation did not repeat a "coded" or iterable utterance, or in other words, if the formula I pronounce in order to open a meeting, launch a ship or a marriage were not identifiable as conforming with an iterable model, if it were not then identifiable in some way as a "citation"? (p. 18)

(Correct answer: No, it couldn't.)

As a consequence:

As a consequence:

The "non-serious," the oratio obliqua will no longer be able to be excluded, as Austin wished, from "ordinary" language. And if one maintains that ordinary language, or the ordinary circumstances of language, excludes a general citationality or iterability, does that not mean that the "ordinariness" in question … shelter[s] … the teleological lure of consciousness … ? (p. 18)

(Correct answer: Yes, it does.)

Thus, the concept of "context" itself gets into some problems too, since it is not clear what counts as a theatrical context, and what doesn't:

Thus, the concept of "context" itself gets into some problems too, since it is not clear what counts as a theatrical context, and what doesn't:

The concept of … the context thus seems to suffer at this point from the same theoretical and "interested" uncertainty as the concept of the "ordinary," from the same metaphysical origins: the ethical and teleological discourse of consciousness. (p. 18)

To round off, he ensures us that his point

isn't that consciousness, context, etc. makes no difference to

meaning, but only that their negative counterparts cannot be excluded

from the picture.

Who Really Talks When You Are Talking? pp. 19–20

|

| Derrida's signature, jokingly inserted at the end of the paper. |

Being thus authentic if and only if they are good copies, signatures thus illustrate the contradiction that is built into the mentalistic notion of writing.

A Last Salute

Perspectives and Additional Claims, p. 20–21

On the last page of the essay, Derrida very rapidly throws a couple of rather large claims at the reader, mixed loosely with a summary of his main points:

- The concept of writing is gaining ground, so that philosophy increasingly relies on authenticity concepts like "speech, consciousness, meaning, presence, truth, etc."

- Writing is difficult to understand from the perspective of the traditional theory.

- His project of insisting on the work done by negative concepts (absence, failure, etc.) can be carried further in a larger project of metaphysical criticism.

So that's a dubious claim, a triviality, and a literature reference.