The title of

this book is a bit misleading; it suggests a sexy collection of provocatively political manifestos but is in fact a piece of good, old-fashioned classicist scholarship, like much of the work Foucault did in his last years.

This particular study is concerned with the notion of

parrhesia or "frank speech," which played an interesting role in both Athenian democracy and later Stoic self-improvement. Foucault combs meticulously through the works of Seneca, Epictetus, Plato, and others, in order to map out how the concept came to be first articulated and then problematized in the ancient and late-ancient literature.

The text is based on

six tape-recorded lectures that he gave at UC Berkeley in 1983.

Although the first couple of chapters of the book treat the role of

parrhesia in the context of political life, it really starts to pick up momentum as Foucault gets into the discussion of his latter-day pet topic,

the care of the self.

The King Gets a Beating

As part of this discussion, he considers a dialogue by the Cynic philosopher

Dio Chrysostom. This text dramatizes the

alleged meeting between

Diogenes (the philosopher said to live in a barrel) and Alexander the Great (pp. 124–133).

During the dialogue, Diogenes provokes Alexander by all sorts of means, including questioning his courage and his claims to the throne. This kind of deliberate provocation has some interesting parallels with the Socratic dialogue, but also some interesting differences from it:

… whereas Socrates plays with his interlocutor's ignorance, Diogenes want to hurt Alexander's pride. For example, at the beginning of the exchange, Diogenes calls Alexander a bastard and tells him that someone who claims to be a king is not so very different from a child who, after winning a game, puts a crown on his head and declares that he is king. Of course, all that is not very pleasant for Alexander to hear; But that's Diogenes' game: hitting his interlocutor's pride, forcing him to recognize that he is not what he claims to be—which is something quite different from the Socratic attempt to show someone that he is ignorant of what he claims to know. (p. 126; emphasis in original)

As the dialogue progresses, Alexander's patience and tolerance are put to increasingly harsh tests. In effect, Diogenes thus turns the conversation into a game with extreme stakes: Will Diogenes shut up out of fear for death, or will Alexander lose his temper and slaughter him because, after all, he did not have the self-confidence and fearlessness that marks a true king?

Everybody Wins?

The martial element of the dialogue is thus, in one sense, even stronger than in Plato:

Whereas the Socratic dialogue traces an intricate and winding path from an ignorant understanding to an awareness of ignorance, the Cynic dialogue is much more like a fight, a battle, or a war, with peaks of great aggressivity and moments of peaceful calm—peaceful exchanges which, of course, are additional traps for the interlocutor. (p. 130)

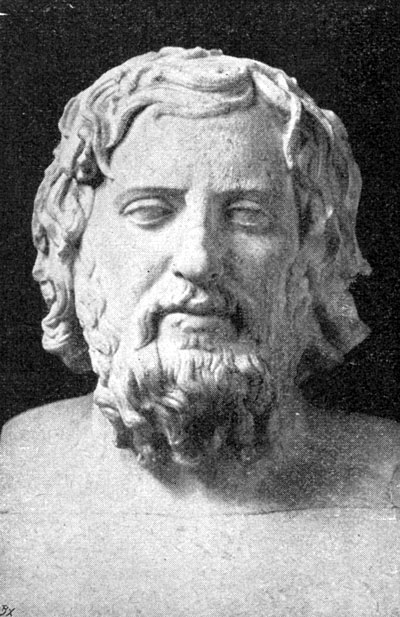

|

| 19th century depiction of the meeting (from Wikimedia). |

The game finally ends when Alexander gets around to asking what the true mark of a king might be (now that Diogenes has disqualified practically everything that makes Alexander a king). Diogenes explains that a true king behaves like one, and is, in what I assume is Foucault's paraphrase, "noble by nature" (p. 132).

Thus:

Here the game reaches a point where Alexander does not become conscious of his lack of knowledge, as in a Socratic dialogue. He discovers, instead, that he is not in any way what he thought he was—viz., a king by royal birth, with marks of his divine status, or king because of his superior power, and so on. He is brought to a point where Diogenes tells him that the only way to be a real king is to adopt the same type of ethos as the Cynic philosopher. And at this point in the exchange there is nothing more for Alexander to say. (p. 132)

Just as in the Stoic

ethos, the goal of the whole exercise thus seems to be a kind of independence from visible fame, power, and wealth. It's not that the real gratification lies in some afterlife as in the Christian tradition, but there is still a sense that one should avoid attachment to the wrong things, and to the wrong symbols.

Perceptual Hygiene

The last example in the book comes from a text by Epictetus, and describes a method for training oneself to meet impressions with the right state of mind. Inspired by sophistical question-and-answer games, Epictetus suggests that we should constantly keep an inner dialogue going regarding everything we see:

As we exercise ourselves to meet the sophistical interrogations, so we ought also to exercise ourselves daily to meet the impression of our senses, because these too put interrogations to us. So-and-so's son is dead. Answer, "That lies outside the sphere of the moral purpose, it is not an evil." […] He was grieved at all this. "That lies withing the sphere of the moral purpose, it is an evil." He has borne up under it manfully. "That lies within the sphere of the moral purpose, it is a good." Now if we acquire this habit, we shall make progress, for we shall never give our assent to anything but that of which we get a convincing sense-impression. (p. 163, cited from Epictetus: The Discourses as Reported by Arrian, III, 8)

Epictetus goes on to recommend doing this exercise constantly "from dawn till dark," interrogating your senses about everything you see. He compares this examination of one's impressions to the caution of a nightwatch — "Wait, allow me to see who you are and whence you come" (p. 161).

This is interesting for two reasons: First, it resonates a lot with contemporary notions of mindfulness as employed in New Age religions and self-help therapy. And second, it has an interesting and not completely obvious relationship with epistemological skepticism; many philosophical discussions of how one should distrust one's senses acquire a quite different ring when we put them in the context of such a clearly normative and ethical theory of perceptual hygiene.

The Dangers of Florid Prose

Just one last example: In his book

On the Tranquility of Mind, Seneca reproduces a (possibly fictional) letter by a family member named Serenus. In the letter, Serenus complains that while he har largely overcome his desire for material wealth, public recognition, and an immortal legacy, he still occasionally falls back into old habits, feeling envy at "the sight of slaves bedecked with gold" and the like (p. 155, cited from Seneca:

On the Tranquility of Mind, I, 4–17).

What I want to point out, however, is the way that Serenus explicitly links his desire for an eternal memory with a specific mode of writing:

And in my literary studies I think that it is surely better to fix my eyes on the theme itself, and, keeping this uppermost when I speak, to trust meanwhile to the theme to supply the words so that unstudied language may follow it wherever it leads. I say: "What need is there to compose something that will last for centuries? Will you not give up striving to keep posterity silent about you? You were born for death; a silent funeral is less troublesome! And so to pass the time, write something in simple style, for your own use, not for publication; they that study for the day have less need to labor." Then again, when my mind has been uplifted by the greatness of its thoughts, it becomes ambitious of words, and with higher aspirations it desires higher expression, and language issues forth to match the dignity of the theme; forgetful then of my rule and of my more restrained judgment, I am swept to loftier heights by an utterance that is no longer my own. (pp. 156–57)

In this way, Serenus (or Seneca) constructs a direct parallel between vain desires and ambitions to "high" writing. Apparently the assumption is that there is a kind of humbleness or honesty built into the "simple style" which at once is guaranteed to be "your own" and to keep you vigilant with respect to abiding by your (Stoic) principles of a philosophical life.

Final Remarks on Method

There is a place in the third volume of the History of Sexuality in which Foucault implicitly criticizes the Marxist conception of the dynamics of history for being to rigid, but it is quite obscure what exactly he imagines to put in its place.

This gets a little clearer in the brief remarks he makes on his project in these lectures. It's an important point, so I'll quote is quite extensively here.

During the first lecture, Foucault states:

I would like to distinguish between the "history of ideas" and the "history of thought." […] The history of ideas involves the analysis of a notion from its birth, through its development, and in the setting of other ideas which constitute its context. The history of thought is the analysis of the way an unproblematic field of experience, or a set of practices, which were accepted without question, which were familiar and "silent," out of discussion, becomes a problem, raises discussion and debate, incites new reactions, and induces a crisis in the previously silent behavior, habits, practices, and institutions. The history of thought, understood this way, is the history of the way people begin to take care of something, of the way they become anxious about this or that—for example, about madness, about crime, about sex, and themselves, or about truth. (p. 74)

In his concluding remarks at the end of the course, he elaborates:

Some people have interpreted this type of analysis as a form of "historical idealism," but I think that such an analysis is completely different. For when I say that I am studying the "problematization" of madness, crime, or sexuality, it is not a way of denying the reality of such phenomena. One the contrary, I have tried to show that is was precisely some real existent in the world which was the target of social regulation at a given moment. The question I raise is this one: How and why were very different things in the world gathered together, characterized, analyzed, and treated as, for example, "mental illness"? What are the elements which are relevant for a given "problematization"? And even if I won't say that what is characterized as "schizophrenia" corresponds to something real in the world, this has nothing to do with idealism. For I think there is a relation between the thing which is problematized and the process of problematization. The problematization is an "answer" to a concrete situation which is real. (pp. 171–72)

Homing in even more specifically on what must have been a Marxist critique, he continues:

But we have to understand very clearly, I think, that a given problematization is not an effect or consequence of a historical context or situation, but is an answer given by definite individuals (although you may find this same answer given in a series of texts, and at a certain point the answer may become so general that it also becomes anonymous). (p. 172)

These answers do not come "from any sort of collective unconscious" (p. 172):

And the fact that an answer is neither a representation nor an effect of a situation does not mean that it answers to nothing, that it is a pure dream, or an "anti-creation." A problematization is always a kind of creation; but a creation in the sense that, given a certain situation, you cannot infer that this kind of problematization will follow. Given a certain problematization, you can only understand why this kind of answer appears as a reply to some concrete and specific aspect of the world. There is the relation of thought and reality in the process of problematization. (p. 172)

I suspect this is about as clear as Foucault ever got on this issue, and about as clear as he could get.